Unless you were raised by a therapist, conflict is not something many of us are explicitly taught growing up. It falls in the bucket of experiential learning and many of us learn what not to do long before learning how to work through conflict in relationships we can’t just hit the eject button on. Anyone who has gone through a painful and contentious breakup can take away something from this book. Getting to Zero: How to Work Through Conflict In Your High-Stakes Relationships by Jayson Gaddis is a fantastic guide for navigating conflict and more importantly, learning how to reconnect after a conflict (disconnect) has occurred.

Jayson’s writing style is easy to digest and this book contains many nuggets of information that couples counseling would set you back hundreds of dollars to obtain. Throughout and at the end of each chapter are prompts to facilitate reflection about your own personal history with conflict. The prompts are thought provoking and at times had me staring out the window in a reflective trance. The author makes the argument early on that conflict (disconnect) is unavoidable in high stakes relationships; the trick is learning how to reconnect after a disconnection has occurred. The author also cautions that avoiding an external conflict only breeds more internal conflict. An insight that really stuck with me was the observation that many of our beliefs about conflict come from observing how our caregivers would engage in conflict and reconnect after, a concept he refers to as our “relational blueprint”. The first high stakes relationship you experience in life is the relationship with your caregivers. Once understood, this past experience can be viewed as an opportunity to increase self awareness about your own personal attachment style.

Disconnection Behaviors

Anyone who has been in a long term relationship will appreciate the insight he surfaces early on about how disconnection is inevitable; thus the real skills to master are how to engage during a disconnect and the art of reconnection. The author provides vocabulary to describe common types of disconnects that occur:

- Posturing: allowing ego to get involved and getting hostile, invalidating, or defensive

- Collapsing: shutting down and withdrawing

- Seeking: making efforts to bridge gap caused by disconnect

- Avoiding: making efforts to create distance after a disconnect

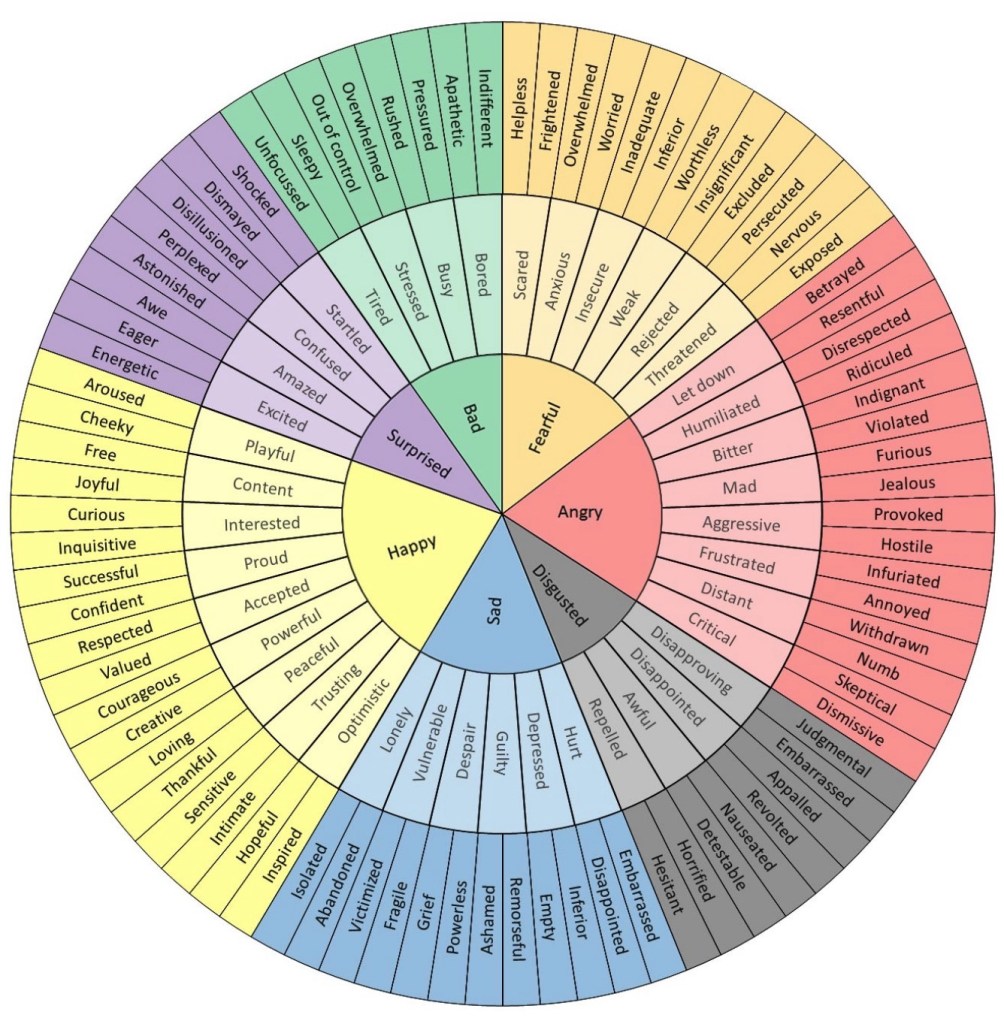

Posturing and collapsing are divergent as are seeking and avoiding; it’s common for partners to disconnect in a polarized way. I’ve noticed in myself that the way I disconnect is typically tied to the emotion I am feeling at the onset of the conflict. For example, when I am feeling betrayed, resentful, or disrespected, I have a tendency to posture, get defensive, or lash out at the other person. However, when I feel helpless, inadequate, excluded, or weak I have a tendency to collapse. I often seek when I feel embarrassed, rejected, or abandoned, but avoid when I feel remorseful or overwhelmed. Oftentimes a mix of disconnection behaviors can be present at the same time such as avoiding and collapsing or posturing and seeking.

Attachment Styles

Once the different types of disconnection are understood, it is easier to identify your own attachment style and which attachment styles are more compatible for you. In general there are four attachment styles people develop early in their life through interaction with their caregivers:

- Secure: depend on their partners and, in turn, let their partners rely on them

- Anxious: deeply fear abandonment

- Avoidant: do not want to depend on others, have others depend on them, or seek support and approval in social bonds

- Disorganized: the relationship itself is often the source of both desire and fear

The last three are considered “insecure” attachment styles and are characterized by difficulties with cultivating and maintaining healthy relationships. While possible to work towards a secure attachment style, the attachment style you possess is theorized to be relatively fixed throughout your life. The author defines secure attachment as one that leaves you feeling:

- Safe

- Soothed

- Seen

- Supported/Challenged

A deficiency in any of these factors is often the catalyst for disconnect in the first place. Recognizing deficiencies in these factors present in your childhood can explain a lot of the attachment style you lean towards as an adult. A lack of attunement at an early age has made me develop into an adult with an anxious attachment style. I have a deep fear of emotional abandonment and have a tendency to seek too hard after a disconnect, leading me to be called “clingy” in the past by romantic partners. I have a hard time with people in high stakes relationships who are avoidant after a disconnect because this triggers one of my deepest fears. Understanding if you are more triggered by closeness or distance in a relationship is a strong indicator of your attachment style. I am more triggered by distance in high stakes relationships.

It’s easy to recognize the other person’s part in not meeting our needs, but often the biggest conflict we possess is the internal conflict raging inside each of us. Jayson borrows some tools from Dr. John Demartini’s book The Values Factor (I earn a commission if you click this link and make a purchase at no additional cost to you) to help the reader determine their highest values, namely a 13 part questionnaire. Thinking deeply about the things you fill your living space with, how you spend your time, energy, and money, behaviors you are most disciplined about, topics you discuss most in social settings, consistent long term goals, and the things you love to learn about most are a necessary step in determining your highest values. Social idealisms, or values that you have determined are useful for getting your needs met, must be examined closely to see if they align with what your highest values actually are. As someone who spent over 20 years in school and has spent the last seven climbing the corporate ladder, the prospect of there being divergence between my “true” highest values and a self developed in response to social idealisms shook me to my core. The larger the divergence in direction between what the book refers to as your strategic self (the self developed in response to social idealisms) and your true self, the more dissatisfied with life (away from zero) you will be. On top of that, it can be hard to find compatibility with others’ values if you can’t articulate your own.

What to Do During Conflict

What to do during a conflict is one of the main draws to this book. The author covers being with your triggers, being with your partner’s triggers, listening to foster understanding, and how to speak effectively during conflict. A key insight is that when we get triggered, a different part of your brain (sympathetic nervous system – the author refers to it as the “back of the brain”) is activated and making decisions. The incentives and courses of action prescribed by the back of the brain are very different than those set by the “front of the brain”. The front of the brain is where most of the “rational” decision making faculties are present; is responsible for many of the idealistic values humanity strives for: being the bigger person, agreeing to disagree, and saving face in an argument. The back of the brain is activated in times of perceived danger to life itself; accordingly, it makes decisions fast to try and get out of the dangerous situation as quickly as possible. Unfortunately, the back of the brain can be hyperactive, over responsive, and may turn on when faced with surface level fights. Anyone who has said something they regret later during a conflict can appreciate that the quick decisions made by the back of the brain have a tendency to be suboptimal with respect to maintaining a secure attachment. Consistently leaving the back of the brain in charge of your decision making faculties is unhealthy; chronic stress has been proven to be an aggravating factor for many diseases. Therefore, it’s wise to be diligent to recognize what triggers you and how it manifests during conflict. The author provides a guided meditation that I’ve found to be useful in recognizing the source of distress. Recognizing triggers and associated sensations and thoughts is a useful first step; learning to increase your emotional discomfort threshold and self-regulate is paramount to staying calm when conflict arises. Sometimes there is no way to remain calm and hitting the pause button is required. As someone with an anxious attachment style, I’m learning the utility of hitting pause to cool down, allowing the front of the brain to get back in the driver’s seat, and attempt reconciliation after a break. It’s difficult, but recognizing that pause and breakup are not the same thing is a distinction I’ve had to learn to embrace.

When it comes to being with your partner’s triggers, it starts with providing the four relational needs to your partner. This can be difficult to provide if you’ve maneuvered through life thus far without having these met for you. If any of those needs go unmet, insecurity regarding the relationship will begin to find its way in. To describe the dynamic at play in a high stakes relationship, the author uses the analogy of two boats tied together in the middle of the ocean. One boat represents what’s right for you. The other boat represents what’s right for your partner. The bond between the two is what’s right for the colloquial us. The ocean represents life and all the challenges that will inevitably come your way. The two of you consented to tying the boats together for some reason, oftentimes because you recognize that you can accomplish more together than you could apart. Remembering the reason why you are in the relationship in the first place and learning to make decisions together that “stand for three” is key to learning how to react to your partner’s triggers. Standing for three is about doing what’s good for me, good for you, and good for us.

The systems proposed around listening and speaking during conflict alone are worth the read. I won’t spoil it for the reader, but will say that waiting to air your grievances until your partner communicates that they feel understood is a central argument. Being mindful of nonverbal communication, speaking in terms of your partners highest values, and not monologuing are also very important.

Most Common Fights

The last section of the book talks about the do’s and don’ts of conflict. The author begins with an overview of the five most common fights. An insightful takeaway for me was that many “surface level fights”, are the tip of the iceberg for a deeper held resentment, issue of security, or value difference. Projections from childhood and previous relationships are unavoidable to a degree in romantic relationships. If you haven’t worked through something from your past, you’re much more likely to project it on to your current partner. Owning this and communicating that projection is going on makes things less confusing for your partner. An issue of security occurs when one partner feels the other one isn’t all in on the relationship. Conflict centered around issues of security in a relationship breed much more intense “surface level fights”.

Values are things you care about and the author provided tools to help identify earlier in the book. Value differences can be deal breakers for many relationships. In my own life, I’ve dealt with value differences regarding growth vs fixed mindset, living in a city vs in a smaller town, and wanting kids vs not wanting kids. Many people adopt the simplified model that “it’s not meant to be” if value differences exist, but the author points out that diversity in values is the driving catalyst for growth in our relationships. Anyone who has been a participant on a successful team can appreciate the sentiment that diversity of values oftentimes pushes the team to grow together to achieve things larger than any of the individual parts. In my own life, I’ve observed this phenomenon in sports, engineering, and business. The same is true in relationships. The author dedicates a whole chapter at the end of the book to resolving value differences that I highly recommend.

Resentments are born out of an expectation of ours going unmet. They manifest as a form of blame that occurs when one tries to get their partner to change in a way that is out of alignment with their partner’s highest values. We harbor resentment when we feel we have been treated unfairly. The issue of fairness is with respect to our own value system. Resentment is often born when one partner is faced with two bad choices: either reluctantly conform to what is being requested and betray themselves or refuse and risk losing the relationship or pushing the requester away. Resentment often goes unchecked, couples keep having the same surface level fights, and the deeper value difference is buried. Resentment left unchecked can lead to contempt (one of the four horseman of the apocalypse according to the Gottman Institute) which is a very strong predictor of divorce in married couples. This highlights an important point the author harps on early in the book that conflict over an expectation unmet must be made known to your partner, preferably immediately. If you avoid conflict and don’t communicate the unmet expectation to your partner, it can blind side them when the resentment is eventually brought to the surface.

Roadblocks to Reconnection

Of course there is a section in the book dedicated to what not to do, ten in total are called out.. There were roadblocks called out that I think most people are intuitively aware of like blame, generalizing behavior to describe character, and using language of the form “you always” or “you never” when engaging in conflict. Blame is interesting because it can be both a form of posturing and collapse. If you blame yourself too hard, it usually turns into a bullshit justification for why you acted the way you did; in this form, is still incongruent with taking ownership of your part in the conflict. That said, it’s impossible to eliminate blame entirely – it’s better to get underneath the blame and begin thinking about what you’re really upset or scared about.

Some of the roadblocks were things I had heard previously from the Gottman Institute like defensiveness and stonewalling. There are more subtle roadblocks to reconnection that the author points out like how apologizing too quickly or too frequently can actually be a roadblock to true reconciliation. Apologies can turn out similar to the “boy who cried wolf” story, eventually the apologies become empty, meaningless words and in some cases are actually a form of posturing to defend the ego from feelings of guilt or shame. Distraction is another subtle roadblock. Unfortunately it’s never been easier to distract ourselves from conflict present in our lives. Work, excessive smart phone use, social media, porn, sex, watching sports, substances, even exercise can be a roadblock to reconnection if relied upon too heavily. The problem with distracting yourself from a conflict is the conflict is still there after your distractionary period is finished. One of the most damaging conflicts to try and distract yourself from is the inner conflict, a lesson I have had to learn the hard way. My favorite roadblock the author described is an acronym he calls FRACKing:

Fixing

Rescuing

Advice

Colluding

Killing

I’ve never felt so personally attacked! All jokes aside, this roadblock has a tendency to be more present in men. Especially men who engage in engineering for a living. Something about our brain just wants to FRACK all of life’s problems away. This commonly leads to the classic complaint that I’ve heard from women in my life that “you/he just doesn’t understand me”. Colluding is an interesting one that I wasn’t aware of until I read the book – commiserating with your partner and attacking the source of their emotional distress is a form of blame. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve had a friend complain about a coworker and my response has been “Fuck that guy!”. I never really connected the dots that this form of blame may in fact be a roadblock to reconciliation. Killing is denying or gaslighting the other person’s experience – “you shouldn’t feel that way” or “that didn’t happen”. No person’s experience is right or wrong – it just is; this is the essence of validation with respect to feelings. My father loves to FRACK so much that I’ve effectively stopped communicating problems present in my personal life to him. It communicates doubt in your partner’s ability to handle the conflict at hand when FRACKing is the consistent, go-to response. Over time, this can erode the feeling of being seen and supported that is required for a secure attachment.

The last section of the book ends with a set of agreements to make with your partner to stay committed to reconnecting after conflict and what to do if the other person refuses to work with you. For anyone who has ever been cut out of someone’s life or not given a chance to reconcile, the section on what to do if the other person refuses to work with you will be very helpful.

Overall, I highly recommend this book. The past can not be changed, but if 20 year old me had taken the concepts presented in this book to heart, a lot of painful heartache may have been avoided. I’ve come to appreciate that the quality of your life is directly proportional to the quality of your relationships. No relationship is without conflict – learning to engage in the least damaging way and reconnect after a disconnect is a skill paramount to living a high quality life. You can purchase the Getting to Zero book here. I earn a commission if you click this link and make a purchase at no additional cost to you.

Leave a comment